Clash of “A Group of Companies”

Confusion often arises when one concept has various nuanced meanings in different spheres. A “group of companies” is one such concept, which has different meanings depending on the context. The concept is defined differently in the Companies Act, in the Income Tax Act and IFRS for example. The concept is also loosely referred to in conversation or the commercial world. However, only the tax concept and meaning (per the Income Tax Act) provides access to special tax relief provisions.

A “group of companies” is defined in the Companies Act 71 of 2008 (Companies Act) as “a holding company and all of its subsidiaries”. On the face of it, the Companies Act definition is very broad. The Companies Act definition is however narrowed with the definition of “holding company” as “a juristic person that controls that subsidiary”. Therefore, a controlling element is added. There is a discord between the Companies Act definition, and the definition for tax purposes.

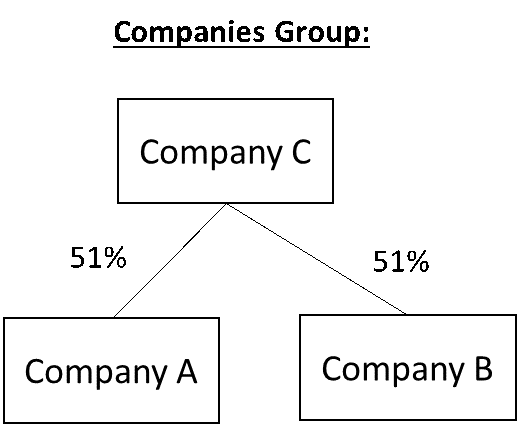

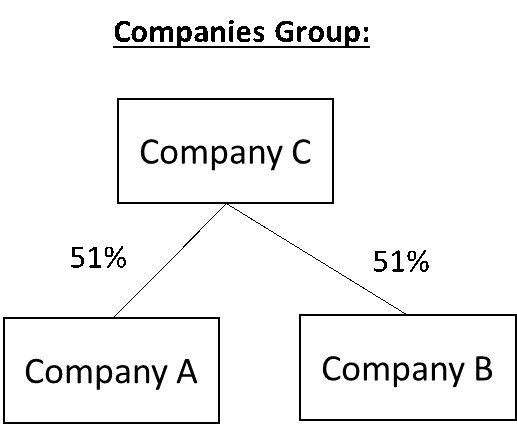

A “group of companies” is provided a different definition in the Income Tax Act 58 of 1962 (Tax Act). For tax purposes, it means two or more companies in which one company (hereinafter referred to as the “controlling group company”) directly or indirectly holds shares in at least one other company (hereinafter referred to as the “controlled group company”), to the extent that—

- at least 70% of the equity shares in each controlled group company are directly held by the controlling group company, one or more other controlled group companies or any combination thereof; and

- the controlling group company directly holds at least 70% of the equity shares in at least one controlled group company.

For tax purposes, a 70% shareholding between companies is required. A tax “group of companies” is therefore a very specific and narrow concept.

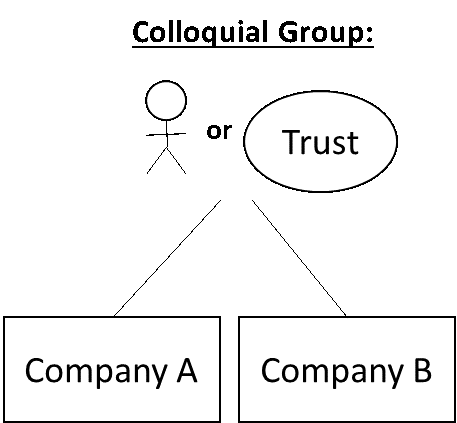

A “group of companies” is often colloquially used as well. It may well be that that you have heard someone referring to his or his family’s companies as a “group of companies”. Despite being (probably) true in the literal sense, the Tax Act requires the top holding entity, to be a company. Should a family trust or the individual own all the shares in various companies for example, there may be an informal “group of companies”, but the definition for tax purposes will not be met and no tax relief can be afforded in those cases, without restructuring being required from the outset.

The different “group of companies” concepts are best illustrated as follows:

Only once it is established that there is a “group of companies” for tax purposes, tax and commercial advisors can look to the application of different corporate rollover provisions contained in section 41 to 47 of the Tax Act to achieve commercial objectives in a tax neutral manner.

The corporate rollover provisions have the effect of deferring normal tax and capital gains tax to a future disposal and could be applied for example when Company A wants to transfer an asset or part of its business to Company B. Generally, the transfer could result in capital gains tax, recoupments, or VAT being due. However, to the extent that one or more of the corporate rollover provisions are applied (as there is a “group of companies”) this transfer would have no adverse tax consequences and there will only be a tax liability when Company B eventually transfers the asset outside of the “group” structure. There are numerous instances in which the corporate rollover provisions can be applied, all which are fact specific and, in many instances, require amongst other things the presence of a “group of companies” for tax purposes.

We emphasise that any restructure should be underpinned by proper commercial rationale and reasons, as SARS could for example attack any transaction on the basis that it is an impermissible scheme aimed at avoiding tax. At the same time, taxpayers are entitled to structure their tax affairs as efficiently as possible, within the legislative realm provided in the Tax Act.

We recommend that taxpayers re-evaluate their shareholding structures from a commercial and tax perspective, as a “group of companies” in the tax sense may prove an effective mechanism to achieve commercial objectives without the hindrance of adverse tax consequences.